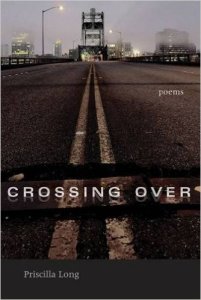

Priscilla Long’s Crossing Over: Poems is unmistakably Washingtonian. The Mary Burritt Christiansen Poetry Series of The University of New Mexico Press announces its mission to “engage and give a voice to the realities of living, working, and experiencing the West and the Border as places and as metaphors.” Crossing Over surpasses their mission. Readers of Crossing Over know where they are at all times—in the western United States, in Washington State. We cross over bridges, tangible and metaphoric, of our state. We gaze at the engineering of a crossing over from a highway pullout, or from below. We cross over metaphorically from Here-and-Now to Then-and-Memory with Long. We cross over metaphorically to death. We cross over to personal realms of sadness, and think of those who have crossed over. We miss them. In many of her poems, Long addresses her sister, Susanne, who has crossed over. Susanne crossed over decades ago, but we understand her continuing influence and presence in Long’s heart.

Priscilla Long’s Crossing Over: Poems is unmistakably Washingtonian. The Mary Burritt Christiansen Poetry Series of The University of New Mexico Press announces its mission to “engage and give a voice to the realities of living, working, and experiencing the West and the Border as places and as metaphors.” Crossing Over surpasses their mission. Readers of Crossing Over know where they are at all times—in the western United States, in Washington State. We cross over bridges, tangible and metaphoric, of our state. We gaze at the engineering of a crossing over from a highway pullout, or from below. We cross over metaphorically from Here-and-Now to Then-and-Memory with Long. We cross over metaphorically to death. We cross over to personal realms of sadness, and think of those who have crossed over. We miss them. In many of her poems, Long addresses her sister, Susanne, who has crossed over. Susanne crossed over decades ago, but we understand her continuing influence and presence in Long’s heart.

Priscilla Long curates the places of her heart—shows them to us and leaves them safe. When a sister dies, especially unquietly, she leaves a gash. Long may travel across the gash with every breath, and with these poems she crosses us over with her. A poem of about thirty words, “Susanne’s Teapot,” packs a big punch with rhymes yoking now and then—now: “Ceramic blue,” then: “tea for us two;” now: “blue of eyes, (the teapot’s blue), then: “before demise,”— and devastates us with her private devastation.

Long takes us to specific spots where she has been. Poems inspired by the Seattle Art Museum’s Kenwood House show muse on Dutch still lives and weave in the dark crossings of the Atlantic by slave ships. She places us in the museum at a specific show, looking at specific paintings, to consider the specific goings on of the day in which the art was created. This reader suspects “Calder” emerged during and after a walk through the Olympic Sculpture Park, and spending time with his Eagle.

In some poems, Long holds us still and the visitors cross over to join her. “The dead have nothing new to say …” when they stop by in “Visitations.” The line repeats five times to tell us how their presence feel to Long, and we feel this unchanging aspect of sorrow with her. When Long read “Green River Blues” at the Bookworm Exchange in Columbia City some years ago, she tolled with a fist knock for each woman she named. I heard the sound of those knocks again when I read the lengthy list of victims of the Green River killer. Her poem remembers them—they join us—and she honors them.

In no way is Crossing Over a downer despite the time spent in many of the poems with the dead and with grief. Long is funny too. (And the death-and-grief themed poems are often resolute—or inspiring, or musing.) From her war-news-jangled mind comes the line, “I pledge allegiance to coots.” “To my Country in time of War” asserts Long’s American conundrum. She arrives at one answer to how she loves/can love our flawed country in loving the species she sights on a walk around Green Lake. She upturns language from patriotic statements, and joins the ranks of Mary Oliver and Louise Gluck as celebrators of local nature.

Long is fond of lexicons. She displays one for each poem. She may define some of these terms, such as the live and dead load of a bridge, or may catalog species. In “God-Trails” Long sets us at the Selah Creek Bridge with an inventory of six species of Yakima County life: sagebrush, bitterbrush, bobcat, badger, burrowing owl, and balsam root. (Some poems she supplies with a logistical epigraph.) The lexicons place the reader precisely where Long intends. Her poems mesh playful diction with this acute precision. I think of Hopkins when I read Priscilla Long. She invents onomatopoeically with “Feel how words bump,/ding, dip, and bop…” in “To Compose a Poem.” In “Calder” she rollicks Hopkins’-style with alliteration and see-sawing tongue twister: “Bud and tendril tender/their mantra to motion,/their canticle to cosmic/convolution, cantilevered to the curve.” And from “To My Country in Time of War,” … “my mind/keeps jangling TV jingo…” and “… canned sadness for collateral damage.” Long is a poetry engineer.

Priscilla Long’s Crossing Over: Poems features more than four dozen poems. There are a couple of sestinas, a few short, short poems, and many thick and rich columnar stanzas. The bridge poems grew mostly from essays she wrote or edited for the history encyclopedia, HistoryLink.org, a free online Washington State history encyclopedia where she was editor for fifteen years. A happy addition to the poems comes in Long’s notes. Here she delivers history behind the poems such as the designer of the bridge, the date of its dedication, the body of water it spans, its best viewpoint, its mechanics, — and none of this information is dry. It is doused with detail.

You can learn more about the poet at PriscillaLong.org and PriscillaLong.com.

***

The Deification by Jack Remick

The Deification by Jack Remick

I decided to read Jack Remick’s California Quartet in a sweep. Trio of Lost Souls (Book Four) came out this fall, so I launched into Book One, The Deification. The novel is a masculine got-you-by-the-throat wild ride, a coming of age and a coming into agelessness myth. Remick starts us on the road with a teenager in a stolen car. Eddie Iturbi becomes a poet in journeying and roosting in San Francisco, a Beat writer’s grave, Fresno, and metaphoric and impossible locations—his memories and hallucinations and dreams. The Deification is pilgrimage, with religious and Beat reference aplenty—homage to the Beats. Eddie’s search for the way to become a poet, and to learn who he is involves mental and spiritual and physical sacrifice on a frightening scale. I do not want to be a poet, went through my mind many times reading what Eddie Iturbie endured to become one. The deification of the title is of the prior Beats by Iturbie and his San Franciscan mentors, and also of Eddie who inherits and absorbs and interprets the Beat Poet ways, and has his huge dealings with edges and death. Remick’s stories are made of strong stuff—blood and guts and seedy life, and grand scale mythic transformations, all at a careening pace. In the reading you can feel the writing, the rush directly from Remick’s brain to his pen–an almost steady sensation of acceleration.