In late 17th-century Russia, houses and taverns were often decorated by a unique form of art: the lubok (or lubki in the plural) were cheap woodcut prints widely sold in markets, most often depicting scenes of everyday life, although also — and surprisingly so, as that wasn’t very tolerated at that time — satire of religious and state figures at times.

Eventually, the lubok became so popular that even the monarchy began producing its own patriotic cuts in the 19th century. But this form of art fell into oblivion after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, and is now mostly known in academic circles or obscure subcultures in Russia.

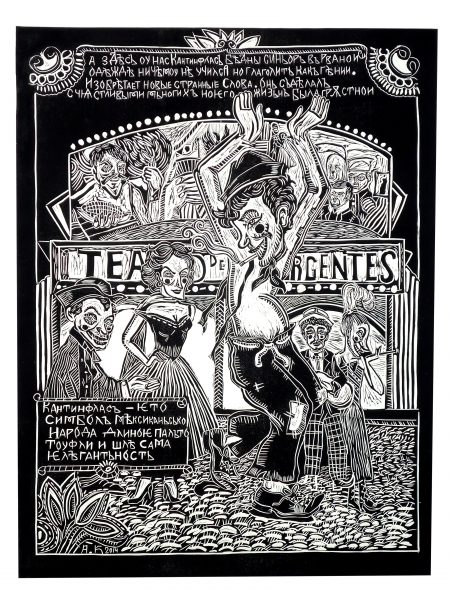

Fast-forward a century later and the lubok emerges across the world in the studio of Mexican engraver Alejandro Barreto, who discovered the tradition as he was learning Russian. He became fascinated by it and decided to produce his own lubki portraying traditional imagery of his native Mexico.

I talked to him about his artistic and intercultural journey. The interview has been edited for brevity.

Filip Noubel: The Russian lubok is part of a very interesting but little known culture, even in Russia. How did you get acquainted with it?

Alejandro Barreto: It happened while I was learning Russian about 10 years ago, I found a lubok engraving in some book, referring to the [image of the] Cat from Kazan [The Cat from Kazan – a city in Russia, is one of the most iconic images of the lubok]. I fell in love at first sight because this was my first encounter, as an engraver, with one of these lubok pieces. It was strange to realize, when I was living in Russia, that ordinary Russians hardly knew about this artistic tradition even though lubok is a living anthropological witness of their history. Children see them in textbooks but they don’t know these images are lubok and how they are made. My main motivation for learning Russian was that it is an exotic language compared to Spanish, which is my native language. I also had a fascination with Soviet cartoons produced by the Soyuzmultfilm studios.

FN: The lubok is sometimes described as the Russian ancestor of satire, comics, and social critique. Do you agree?

AB: The Lubok is a historical document in itself, providing a fabulous amount of information that is valuable for all aspects of the 18th and 19th centuries, when it had its peak. It provides information about the way people lived in rural areas that are known today thanks to these engravings, songs, anecdotes, legends, gossip [many lubok have, besides images, texts incorporated into their frame]. Lubok was a printed means of communication full of humor that could address any issue, just as European gazettes did then, or newspapers do today. I have always thought that the low price [of the lubok printed on thin paper], the humor, and the colorful colors hooked the audience. People would buy the prints and even decorate their houses’ doors or walls.

FN: How do you use the Russian lubok in your art and collection process? How do you share your passion in Mexico and online?

AB: For me, the Russian lubok is a great source of inspiration and an object of study. To be able to understand and adapt it to Mexican culture, I did a PhD thesis in Mexico that explained the history and rules of this art compared to the popular graphic of the Taller de Gráfica Popular [a leftist artist collective founded in Mexico in 1937] with people like Manuel Manilla and José Guadalupe Posada. The popular Mexican graphics shared with the lubok the same kind of stories and humorous prints. I felt that this was the best example to help Mexicans understand what a lubok is and what it represents in Russia. My work led to a process where I had to appropriate the tools and crude style of the lubok to create prints that talked about Mexico’s popular culture and its history. I called the series lubokus.ru.mx, and managed to make a large collection of pieces related to this Mexican-Russian theme. I presented them in exhibitions in various parts of Mexico, Russia and abroad. In 2019, Bulgaria and Poland exhibited them.

FN: How does the lubok relate to other forms of pop art that you collect?

AB: The Lubok is, without a doubt, the predecessor of Russian comics. I think they played a big role in developing modern Russian comics books and are also the precursor of Soviet propaganda posters. I found very interesting similarities with popular engravings of other cultures in terms of format and history, such as the Cordel literature of northeastern Brazil, which displayed rhymes and popular narratives and were sold inexpensively. I had the opportunity to make my lubok art revolve around a very Mexican theme, the Lucha Libre [wrestling]. I have also seen other art forms that share many similarities with lubok, such as the Patua scrolls from Bengal and India, or the lubok that I have seen in other post-Soviet countries such as Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan.

FN: What do you like most about lubok art?

AB: I have been a fan since I have started studying the lubok and I have made prints inspired by them. During my visit to Russia, I was able to obtain some original lubok prints illustrating various subjects, including Bible engravings illustrated by Vasily Koren (the first Bible printed in Russian in 1692 that launched the technique of wood engraving that preceded the one used for the lubok) but also anecdotes, unusual facts and satirical political stories.

I love the aesthetics of the figures represented in lubok. I realize the ingenuity of the Russian people of the time. These prints were interpreted in a very pure way in the face of extraordinary events, that is to say that they depicted exotic animals or monsters without having a real reference or photograph. The representations were based on stories and they made wonderful characters, coming from a naïve form of art.

FN: Can the lubok relate to a form of Mexican culture, art, or humor?

AB: As I said before, in Mexico there was a very important period of Mexican engravings coinciding with the building of our nation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when our country was being restructured. At the time, Mexican culture began to experience its first glimpses of modernity. The government and the powerful classes were very repressive, and that [repression] shaped the conditions so that engravings would become, too, a weapon of protest. It was accessible, it spoke for the people, it raised a voice of criticism and humor. In my view, a healthy nation must have a sense of humor and be self-critical. Both the lubok and our Mexican engravings share that chapter in their respective stories.

More of Barreto’s art can be seen on his Instagram account. Filip originally wrote this for Global Voices.