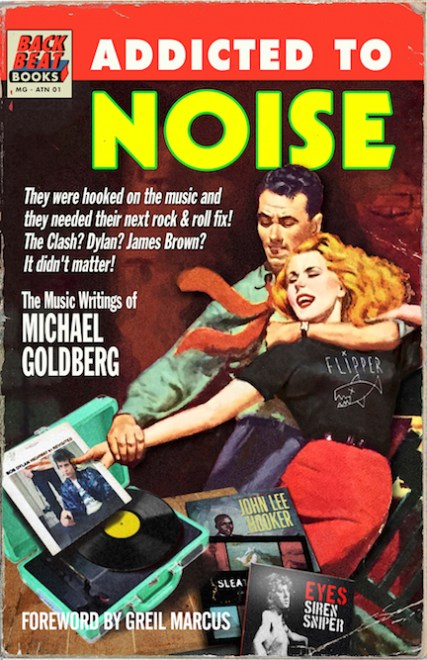

Michael Goldberg, doyen of music criticism (or rockcrit, even), returns with his new book Addicted To Noise: The Music Writings of Michael Goldberg, with an introduction by Greil Marcus, containing interviews, profiles, essays, and stories covering Patti Smith, Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Lou Reed, Laurie Anderson, the Ramones, the Sex Pistols, John Lee Hooker, Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart, Tom Waits, Flamin’ Groovies, Flipper, Black Flag, the Replacements, Crime, the San Francisco Scene, the Mabuhay Gardens, Gil Scott-Heron, John Lee Hooker, Robbie Robertson, and so on.

He was kind enough to take some questions over email.

****

Seattle Star: What in your childhood and adolescence made you want to write–which writers, books, stories, articles, etc.?

Michael Goldberg: I was a serious reader from when I was a young kid. I loved Treasure Island, Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, Sherlock Holmes stories, Agatha Christie, later Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, and still later Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment.

When I was 12, after hearing the Beatles, I read 16 Magazine, one of the few magazines then that covered the Beatles and other rock and pop groups of the time. When I was in high school I loved Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Tender is the Night, J.D. Salinger and Kerouac. On the Road was major for me.

I read music critic Ralph J. Gleason in the San Francisco Chronicle, and Michael Lydon in Ramparts. In 1967 I subscribed to Rolling Stone–probably with the second or third issue. I became a big fan of Greil Marcus, Jon Landau, Rolling Stone founder/editor in chief Jann Wenner (who did a bunch of Rolling Stone Q&As), Robert Duncan, Dave Marsh, Lester Bangs, Ellen Willis, Ed Ward, John Morthland, and others. I remember reading a Q/A in Rolling Stone with Keith Richards when I was in high school and deciding I was going to be a music journalist.

Already I was taking photos of musicians, starting in June 1967 with the Doors, Big Brother and the Holding Company and others at the first rock music festival, which took place on Mt. Tamalpais in Mill Valley less than a week before the Monterey Pop Festival. I loved to write and I wanted in to the world of rock & roll, and I could see that as a rock photographer and writer I’d have access to that world. And I wanted to share my thoughts and observations about music with others through writing.

Seattle Star: What are your earliest memories of music in your life? How did your relationship to music grow and change as you went through childhood and adolescence?

Michael Goldberg: My dad used to play jazz albums in our living room, and took me to see Miles Davis in the early ’60s when he played a concert in Berkeley. I remember Miles standing with his back to the audience and leaving the stage at times while his band played. That wasn’t what most musicians did but that was Miles. I became a fan of rock music in 1964 after seeing the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show, and also hearing the Beach Boys “Fun Fun Fun” and loving it. I had a transistor radio and I would lie in bed at night listening to KFRC and KYA, two Bay Area Top 40 stations in the mid-’60s. My dad hated rock & roll and I’m sure that had an impact 😄 I just became a huge music fan as soon as I heard some rock & roll songs. My dad wouldn’t allow rock records in the house but I didn’t care. I bought Meet the Beatles and hid it under my bed. I bought a Beatles poster and had it taped to my door. I started to collect Beatles bubble gum cards and had 50 to 100 of them on my wall. As I got older my musical interests expanded. I dug British Invasion bands and the Byrds and Lovin’ Spoonful and Blues Project and Bob Dylan and the Mothers of Invention and Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band. I got interested in the blues, Muddy Waters and John Mayall and Howlin’ Wolf, and ’50s rockabilly and Elvis, the Wailers and Toots and the Maytals and other reggae artists. And I became interested in the recording of albums. I loved being in the recording studio and at the offices of record companies talking to the execs there, learning about the record business and the touring business. I became a fan of many rock photographers. Annie Leibovitz, Jim Marshall, Herb Greene, Bob Seidemann, Baron Wolman…

Seattle Star: Which evening did you see the Beatles on the “Ed Sullivan Show”? Had you heard anyone talking about the Beatles before? What were your immediate impressions? Was everyone talking about the Beatles after the shows?

Michael Goldberg: The first show I saw was on February 16. I was riveted. While they played the rest of the world faded away. It was the greatest thing I’d experienced up until that time in my life. I missed the Feb. 9 appearance. After it kids I knew were talking about it. I was cynical. What’s all the excitement about? Well, on Feb. 16 I found out. After I saw them I had to have Meet the Beatles. I remember really being moved by “I Saw Her Standing There.” When I was a kid and I heard rock songs, I totally related to the lyrics. “She Loves You,” “All My Loving,” “From Me To You,” “I Saw Her Standing There.” I listened to those songs and I saw girls that I liked.

Seattle Star: When did you begin to take photographs, and who influenced you in terms of photography?

Michael Goldberg: I had a Kodak Brownie camera that took 120 black and white film. The first time I took photos of musicians was on June 10, 1967 at the KFRC Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival. I took photos of members of Big Brother and the Holding Company–Janis Joplin and guitarist Sam Andrews–and also The Doors. I think I only had one roll of film – 12 shots – so I probably only shot those two bands. The Doors went on last on the first day and I saved most of the roll for them.

Seattle Star: How did you get into the Festival? How did it compare and contrast with other festivals?

Michael Goldberg: The festival ran for two days. It was $2 a day. I bought tickets. There was a place in Mill Valley where you were supposed be at a certain time in the morning and they had buses that took you up to the Mountain Theater, an amphitheater on Mt. Tam where the concert took place each day. I got as close to the stage as I could so I was very close when I took the photos. I got a few good ones which are in my new book.

It was the first rock festival. It was incredible. It’s been reported that as many as forty thousand people attended the two-day event. Didn’t seem like that many people. I would say eight thousand. There were all kinds of hippie booths in the woods around the Amphitheater where you could get food and clothing and incense and jewelry and all kinds of other things. So there were a lot of people who weren’t in the Amphitheater, which can supposedly seat four thousand. Some people didn’t stay for the whole day.

It was the best rock festival I ever went to. It was at the peak of the counterculture in the Bay Area. Lots of beautiful people, most older than me. The sound system was excellent and the bands sounded great! It didn’t feel like a big commercial event. In fact it was a benefit for the Hunters Point Child Care Center in San Francisco.

Seattle Star: What about that first issue of Rolling Stone inspired you to write about music?

Michael Goldberg: There had not been a serious “adult” magazine devoted to rock music before Rolling Stone. There were serious articles in newspapers and some magazines but nothing completely devoted to rock music. I wasn’t aware of Crawdaddy or Mojo-Navigator Rock and Roll News though they were before Rolling Stone. Still, they didn’t include serious reporting, as I recall. Rolling Stone just had a different vibe to it back then. It seemed really cool. When the new issue showed up in the mail I’d bring it to school and read it in class when various teachers were lecturing. Rock & roll was way more important than anything those teachers had to say, I thought at the time. In junior high school I had a rock poster business and tried to sell handbills and posters to kids at school, but that didn’t really take off. Some friends and I put on dance concerts at Tam High in the school auditorium and for a while I thought maybe I’d be a concert promoter. I put together a light show troupe, and me and my friends did a light show at a concert we put on that Michael Bloomfield headlined. During the summer of 1970 a friend and I published one issue of Hard Road, a Bay Area music magazine; an interview we did with Jerry Garcia was the cover story. For a while in the mid-’70s, after I’d been writing for a number of years, I managed a friend’s country-rock band. But from high school on I wrote about rock music.

Seattle Star: How long did you contribute to Rolling Stone? When were you hired full-time?

Michael Goldberg: I began writing for Rolling Stone with a freelance story about Carlos Santana in 1980, and I did freelance pieces on Rick James and Van Morrison and the advent of independent record companies like 415 and Slash in the late ’70s. I was hired as a full time senior writer at the end of 1983. I contributed until around 1994 and then I did a piece on Jimmy Wilsey in early 2019, and they excerpted part of a chapter from my Wilsey book in 2022.

Seattle Star: What are your proudest achievements at Rolling Stone, and why did you eventually leave?

Michael Goldberg: I was the main writer for a cover story on Live Aid, and wrote the “Boy George’s Tragic Fall” cover, a Stevie Wonder cover, a James Brown cover, three Michael Jackson covers, a feature on post-punk which includes Black Flag, Flipper, the Replacements, Husker Du and others (I rode in a van with Black Flag from LA to Las Vegas), a Lindsey Buckingham profile, a Robbie Robertson profile, stories on Brian Wilson and Dennis Wilson, investigative stories on payola and the mob’s infiltration of the record business.

I was on staff for about a decade and had one or more stories in nearly every issue. I went to work for the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1994, putting together exhibits, gathering materials from musicians (my former Rolling Stone editor had become a top exec at the Hall of Fame, which hadn’t opened yet).

Seattle Star: Which other music writers have been your friends across the years, and what do you value from which?

Michael Goldberg: I met Ed Ward and John Morthland (who both wrote for Rolling Stone and many years later wrote for me at Addicted To Noise) when I was in high school. A friend and I would drop by their place (they shared a house) in Sausalito and we would hang out. Ward would play music, tell us stories about musicians he’d written about and sell us promos he didn’t want for $1 each. I got an extra copy that he had of the New York Dolls first album.

I met Dave Marsh at his place when Marsh was editing Creem and had come out to the West Coast for a visit. Marsh later wrote for Rolling Stone and much later Addicted To Noise.

Ed Ward was a great writer and I learned a lot from reading his writing. I learned a lot about country music from the book John Morthland wrote about the beset country records. I learned a lot from reading Greil Marcus’ columns and reviews and books. I dug Lester Bangs’ writing. I soaked up a lot from reading Creem and Rolling Stone and in my 20s I subscribed to the Village Voice and there were many great writers who contributed to the Voice. [Robert] Christgau was editing their music section.

Seattle Star: You mentioned being influenced by Ed Ward’s work. What important things did you get from him? Where and when did you hear that he’d died, and what went through your mind?

Michael Goldberg: Ed was the first rock critic I actually got to know. As I recall I’d read a piece on Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen he wrote for Rolling Stone that was great, and I got their first album and went to see them because of that review. That was before I met him.

After Rolling Stone he became the arts editor at a new Bay Area magazine and they were looking for writers. I called him or sent him a letter and ended up meeting him and asking him a lot of questions about Rolling Stone and being a rock critic.

He wrote an incredible piece about the “5” Royales album Dedicated To You for Greil Marcus’ [book] Stranded. It was a piece of fiction and it was wonderful. It made me aware that you could do unconventional things like write an extended essay as if it were factual but actually make it all up, and in his case, convey more about the actual group than most writers could do writing a non-fiction essay.

He often told stories when he wrote about music in the late ’60s and early ’70s and that made a big impression on me. But there were many other writers that I learned from too.

I read that he’d died right after it happened, back in early May 2021. He was 72, which is young to die. I felt bad. He’d had his ups and downs over the years from what I read. I’d been out of touch for probably 20 years at that point, maybe a little longer. I know he did some great work for NPR. I felt terrible when Lester Bangs died and when John Morthland died. When someone dies young–very young in the case of Lester–it’s a particularly sad situation.

Seattle Star: You were amongst the few who heard “Money Changes Everything” before Cyndi Lauper recorded it. When and where did you hear the song for the first time? What were your thoughts, and did your views on it change from the original indie version, to the Brains’ album version. to Lauper’s version?

Michael Goldberg: I thought it was a killer song, a killer record and the album version was great too. I probably first heard the indie single played on KSAN, the San Francisco FM station. Then I was sent a promo of The Brains album before it came out. I love both versions. It’s one of the great rock & roll songs, right up there with the Groovies’ “Shake Some Action.” It’s obviously a very cynical song, but I think very true. I used it at the end of my piece on the end of KSAN as a progressive rock radio station, because it really seemed to sum up what had happened to that station. I was never into Cyndi Lauper’s version. I love the rawness of the indie single but Tom Gray’s voice is just incredible on the album version too.

Seattle Star: What gave you the idea to launch an internet music publication, and how did you go about launching it?

Michael Goldberg: In 1993 I joined America Online and there was a music chat area, and seeing that, I began to think about how you could do a music magazine at AOL. I started making notes on what it could be like and I approached a guy I knew at a record company, and suggested to him that perhaps the company where he worked would want to fund this online magazine that I had conceptually developed.

He thought it was a great idea and he put me in contact with some execs there but ultimately, after a year, they passed on it. When I then suggested that this guy and I get the thing going on our own he wasn’t interested.

Meanwhile, during that year a browser for the World Wide Web had been created and there were some websites, and I could see that the web would be way better for a music magazine because you could integrate photos and audio and text on the same page, which you couldn’t do at that time at AOL. Plus you wouldn’t have to deal with AOL. So then I completely revised my music magazine concept.

I wanted to create an online magazine that covered music that I thought was great and for the most part that’s what we did. I came up with the name Addicted To Noise and got Frank Kozik, the incredible poster artist, to create a logo and headers for columns and various sections of the magazine and got a lot of writers to agree to contribute including Dave Marsh and Greil Marcus and Richard Meltzer and Billy Altman and David Weiss of the group Was (Not Was) and many many others.

I worked with some young programmers including Jon Luini to create the original Addicted To Noise. I was the founder, publisher and editor in chief of Addicted To Noise. We went live on Dec. 1, 1994.

Seattle Star: How long did Addicted to Noise last, and why did it end? What are your proudest accomplishments there?

Michael Goldberg: Addicted To Noise ran from Dec. 1, 1994 until around March 2000. In 1995, based on me creating Addicted To Noise, Newsweek included me in their “Net 50” of “the 50 people who matter most on the Internet.” In 1997 I was in debt and running out of money, so I sold the company to Paradigm Music Entertainment who had just bought New York’s SonicNet, and I became a Senior Vice-President at SonicNet.

The next three years were incredible. We had lots of money to work with so I could realty develop an in-house staff as well as a huge network of freelance writers. Although Addicted To Noise continued as a separate website, my focus really shifted to SonicNet and in particular, the music news section that I had started at Addicted To Noise but that we renamed SonicNet Music News. SonicNet Music News became like a daily online music newspaper.

At one point I had seventy people working for me: I think that was the largest editorial staff for any music publication. SonicNet Music News became the primary source of music news in the world in the late ’90s. Addicted To Noise ended in 2000 not long after MTV bought SonicNet from TCI Music, who had acquired it from Paradigm. MTV shut it down.

Seattle Star: Richard Meltzer has a reputation for being hard to rope in. How did you manage working with him?

Michael Goldberg: I had enlisted Richard back in around 1979 to write a TV column for Boulevards, a monthly city magazine where I was managing editor. I reached out to him and he was into it. One of his columns for Boulevards was reprinted in his book, “L.A. is the Capital of Kansas: Painful Lessons in Post-New York Living,” a collection of his articles. There’s also one of his Boulevards column in his collection, “A Whore Just Like the Rest of Us.” He was very professional. He always got his column in on time. So I reached out to him again in 1994 when I was starting Addicted To Noise. More recently, I did a lengthy interview with Richard about Jack Kerouac for the book “Kerouac on Record.”

Seattle Star: When it comes to Devo, most people consider Mark Mothersbaugh the cheery prankster, Jerry Casale the brooder with the dark soul. How did they come across to you?

Michael Goldberg: I first interviewed the whole band in 1978 before their debut album was released, at Neil Young’s manager Elliot Roberts’ office in L.A. Roberts (now deceased) was also managing Devo at the time. I wrote a profile of Devo for New Times, a really cool national magazine. So in 1981 when I reached out again to interview them, they were comfortable with having me around in L.A. while they were working on a video for their New Traditionalists album.

They came across as smart, at times sarcastic guys. The second time I spoke to them they had been attacked by critics and they were fed up with that. But they seemed focused on their art. I liked Mark and Jerry a lot.

Seattle Star: How did you manage to gain access to Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch, when Jackson himself wasn’t around?

Michael Goldberg: As I recall, I said to Jackson’s manager that since Jackson himself was not going to participate in an interview, that if there was going to be a Rolling Stone cover story, I needed something special and suggested that they let me spend a couple of days up at Neverland and that’s what happened. No print reporter had ever been there when I went up there.

I got there in the late afternoon and his cook made me some dinner which I ate in his house, then I spent the night in a guest cottage near the house and then toured the house and property the next day. I might have spent two nights up there. It was amazing to be able to check the place out. He had his private zoo and an amusement park with rides and a freestanding movie theater.

Seattle Star: The only time you ever met Jackson, you describe him as almost completely nonresponsive. How did this meeting happen? Were you shocked by his demeanor?

Michael Goldberg: Jackson was rehearsing at an auditorium in L.A., and I was invited there as I was working on a cover story about Jackson and his new album, Dangerous, for Rolling Stone. Various people who were attending the rehearsal, got to “meet” Jackson, one at a time.

It was very brief. There were people who worked for Jackson there and one person would go up to him, he’d shake the person’s hand (he was wearing a glove on the hand he used to shake your hand), and then the person had to leave and the next person came up to him. There was no actual exchange. He was disconnected, just going through the motions.

I wasn’t surprised. I had no expectation that it was going to be any kind of real interaction. If he had been engaged and got into a conversation with me, that would have been shocking. At that point it had been years since he’d spoken to the press.

I had previously worked on two Jackson cover stories, and he wasn’t available for either of those. I would talk to his producers, musicians who played on his albums, people who worked at the recording studios he used and so on. There were lots of people who’d worked with Jackson and been around him who I could interview to put together a compelling story.

Seattle Star: Lou Reed didn’t directly answer your question about how his then-new relationship with Laurie Anderson revived him; he pivoted to discussing himself. Any regrets for not pressing him on that subject?

Michael Goldberg: Not really. I think it’s a good interview. I interviewed Reed for Addicted To Noise, and the focus on Addicted To Noise was music. It wasn’t a musician’s personal life, it was music. If a musician wanted to talk about other things, that was fine, but I wanted them to feel comfortable talking about their music, their recordings, how they made a particular record. I like how he answered my questions. When I asked him whether his relationship with Laurie Anderson had revived him, he said, “I feel like I walked into one of those 40 billion new galaxies that Hubble found. That’s what I think. Lucky me, major domo lucky, that’s what I would say. …” What more did he need to say?

Seattle Star: Reed had such passion for Lorraine Ellison’s “Stay With Me,” and such frustration that he couldn’t play it for you. “I’d tie you up and make you listen to this thing–well, I’d let you do it voluntarily.” Did you ever manage to hear the cut? If so, any thoughts?

Michael Goldberg: Yes, I listened to “Stay With Me” a number of times. It’s a beautiful, passionate song. A real heartbreaker. Her voice is amazing. What a singer!

I was surprised the first time I listened to it. It revealed a side of Reed I wasn’t aware of. I guess I should have been. But I thought of him as cold and angry and this song is so romantic. I thought of him as the guy who trashed Robert Christgau on a live album and who got into arguments with Lester Bangs and wrote about the darkest parts of life. The guy who recorded Metal Machine Music.

Seattle Star: Van Morrison cancelled the second half of your interview without so much as warning you. Did you try to schedule a make-up session? If so, what transpired?

Michael Goldberg: I met with Morrison at a restaurant in Mill Valley. We probably talked for 30 or 40 minutes, maybe more. I had enough to write a story but he did end the interview before I was finished. He was so touchy.

So I asked if we could finish the interview on another day and he told me to come to his house on such and such a day and gave me his address. As I wrote in my story, he wasn’t home when I got to his house. I waited for a while in his garden. Eventually he pulled into his driveway and came into the yard, but tensed up when he saw me. I walked up to where he was and he said he couldn’t do the interview that day and wanted me to call him on Monday. When I called he didn’t answer. I tried a few more times but he never picked up.

So I wrote the story based on the interview he had done with me. It was the lead music story in Rolling Stone. I see that story as really key to me getting hired as a staff writer. It’s really well reported and one of those stories that few people could have gotten.

Seattle Star: You did get to interview Morrison in a low-key manner at a local restaurant. Did you find him shy, evasive, diffident, lost in his own thoughts, or some combination of these?

Michael Goldberg: He seemed nervous, distracted and guarded at first. He was uptight and touchy. I did my best to go with what he wanted to talk about, but it was tricky and if he didn’t like a question, he wouldn’t answer it. He wasn’t evasive, he was very out front about what he would talk about and what he wouldn’t talk about. And he wanted to make it clear that at that point in his life he had no interest in rock & roll and didn’t see his music as having anything to do with rock & roll.

Seattle Star: You’ve pried interviews out of both Morrison and Brian Wilson. Which did you find it tougher to work with, and why?

Michael Goldberg: I don’t look at it that way. I didn’t do any prying. They were completely different situations. In the case of Morrison, I knew that at the most, I’d get a couple hours with him. With Wilson, I spent three or four days hanging around with him and interviewing him and, separately, his manager/therapist Eugene Landy. Landy wanted a big story about Wilson in Rolling Stone, as did Warner Bros. So they all did everything they could to make the Brian Wilson story happen. I had access to pretty much everyone I needed to talk to.

Seattle Star: Flipper seemed quite down-to-earth when you interviewed them. What struck you hardest about their early live shows? Did you enjoy any of their albums nearly so much as the first?

Michael Goldberg: Flipper were/are cool guys. Sadly, Will Shatter is no longer with us. Flipper and I met at a bar in downtown San Francisco that they liked and we talked for a couple hours. I was a freelance writer at the time and was writing a feature for the San Francisco Chronicle’s Sunday Datebook, which was the paper’s entertainment section.

The guys in Flipper thought it was funny that the Chronicle finally wanted to write about them after they’d been together for like three years. They didn’t understand that the Chronicle couldn’t care less about them; it was me that liked their album, which was called Album–Generic Flipper. So there was some joking on their part about the “pink section,” which is how a lot of people referred to the Sunday Datebook, since it was printed on pink newsprint for some reason.

They had a very loose attitude when they did live shows. They’d stand around drinking beer, invite members of the audience to come onto the stage and sing. Every show was a little different. The songs on the first album were very intense and great. The lyrics were written, depending on the song, by Will Shatter or Bruce Lose (later Loose). Yeah I liked the other Subterranean Records recordings, but Album–Generic Flipper is the one that I still listen to.

Seattle Star: In the Sleater-Kinney interview, I notice Corin Tucker didn’t say much in the early going, then seemed to warm up to the questions. Any idea why?

Michael Goldberg: I don’t think that’s accurate. Corin answers the very first question and then she answers others as the interview continues. Maybe she got more comfortable as the interview progressed.

They all knew I was a serious fan and that I was the editor of Addicted To Noise. They seemed really into it. They knew that I wanted to talk about their music and not their personal lives and they could see that was the case as I asked questions.

I thought that in the mid-to-late ’90s they were the best rock band. They had a very original sound and the way their vocals and guitars played off each other was striking. Their lyrics are brilliant. They’re very smart and creative and there’s a lot of depth to their songs.

Seattle Star: Did Sleater-Kinney hold your interest over the years? What about their side projects, and their work without Janet Weiss?

I think my favorite albums are Sleater-Kinney, Call the Doctor and Dig Me Out, but I also like a lot of The Hot Rock and All Hands on the Bad One and One Beat, and I like their recent comeback albums too. I like Corin’s solo albums. Not as much as the Sleater-Kinney albums, but I like them.

I thought Corin’s pre-Sleater-Kinney recordings when she was in Heavens to Betsey are good, same for Cadallaca. I like Carrie’s other projects as well. They were great when Janet was in the band and they’re still great.

Seattle Star: For those of us who weren’t there, what was radical about early KSAN-FM programming, and Tom Donahue in particular? How did Donahue’s approach compare and contrast with his son’s work as radio DJs?

Michael Goldberg: In 1967 Donahue took over programming for a foreign-language FM station in San Francisco, KMPX, and created free form progressive underground radio. His DJs would mix unreleased recordings by Janis Joplin, for example, with album tracks by current underground rock bands, the occasional piece of classical music, Ravi Shankar’s sitar music, blues, folk and other recordings.

In an article for Rolling Stone about AM radio titled “A Rotting Corpse Stinking Up the Airwaves,” Donahue wrote of KMPX, “… It is a format that embraces the best of today’s rock and roll, folk, traditional and city blues, raga, electronic music, and some jazz and classical selections. I believe that music should not be treated as a group of objects to be sorted out like eggs with each category kept rigidly apart from the others, and it is exciting to discover that there is a large audience that shares that premise.”

In the late hours of the night and early morning, there was a blues/R&B show by a DJ called Voco. The DJs were super hip and part of the SF hippie scene. There was nothing like KMPX anywhere in the country when Donahue started programming it and everyone in the Bay Area who was young and into the counter culture listened to it. They would announce free concerts in Golden Gate Park, have musicians like John Mayall on to play records. It was radical programming.

In 1968 after problems with KMPX’s owners couldn’t be resolved, Donahue and members of his staff moved to KSAN in San Francisco. The programming was progressive and still quite radical, at least at first. I don’t recall listening to Sean Donahue on the radio, so I can’t say how his DJing compared to Tom Donahue’s programming.

Seattle Star: How did your first piece about James Brown, in the book, conceptually set up the second piece?

Michael Goldberg: The first story about James Brown was written for Boulevards and also appeared in New Musical Express in England, a profile of the great singer/songwriter/performer who pioneered funk, grounded in a trip to San Quentin prison where Brown performed and was horrified that nearly all the prisoners were either Black or Latino men. It told Brown’s story and was a very positive, admiring piece.

The second piece, a Rolling Stone cover, was written after Brown, high on angel dust, had threatened a room full of people with a gun and then engaged in a two-state car chase with police. It told of the dark side of James Brown. How he had treated friends and musicians who worked for him, as well as girlfriends and his wife at time. It was a very unflattering story.

Seattle Star: You’ve confessed your mixed feelings about the second James Brown piece. What were the pros and cons of writing it, publishing it? How do you feel about it sitting in your chair, today, right now?

Michael Goldberg: Before I wrote that second story, everything written about James Brown was positive. At the time I thought it wasn’t fair to the people including musicians who worked for Brown, and for women he had mistreated, for the real story of who James Brown was to be concealed. Yes, he was a brilliant creative genius. No question. But that doesn’t make him above the law. I did serious reporting and that story is the result of what I found out. Today I remain glad that it was published, which is why I included it in my book.

Seattle Star: I noticed that you’ve redacted the “n-word” where you originally spelled out the word. What inspired you to do this?

Michael Goldberg: There is no way the mistreatment of music artists or visual artists should be compared to the terrible suffering Black people experienced. And using the phrase ‘Rock & Roll N-word’ does just that. It’s like people saying, ‘Well all lives matter.’ Well yeah but Blacks have been treated like shit and hung and tortured and made to be slaves. That did not happen to white people. That did not happen to white rock & roll artists or white painters.

Seattle Star: In 1975, you were poised, mentally and spiritually, to become a “great writer,” in your own words. What were the biggest surprises, biggest disappointments, and biggest revelations, on the trip up the time stream? Do you think you fulfilled your vision for yourself?

Michael Goldberg: I worked really hard over the years on my reporting and writing. I think I became the best writer I could become (and I’m still learning). I also became a good editor, which was not something I had anticipated when I started writing in the late ’60s.

Looking back as I’ve done putting the book together, I’m proud of the work I did over the years. I was overjoyed when Rolling Stone music editor Jim Henke (sadly no longer with us) hired me in late 1983. I spent the previous nine years focused on getting a job at Rolling Stone but still, for it to actually happen was mind-blowing.

My one real disappointment is that I never interviewed John Lennon or Bob Dylan. Those two guys meant a lot to me when I was a teenager. I’m really proud of my Robbie Robertson profile. I spent about year working on it (along with other stories)–I was able to put the passage of time into that story and also I saw him in a number of settings (including up in Woodstock where the Band recorded the Basement Tapes with Dylan and worked on their Music From Big Pink material), which are in the story too.

Often when doing profiles I’d spend a day or two hanging with an artist, do phone interviews with other sources and then write the story – the whole thing might take two, three, four weeks. I feel like I really had the time to do something special with the Robertson story. Lou Reed turned out to be a really nice guy; I had expected him to be very difficult but he wasn’t. That surprised me.

Possibly the most exciting moment of my career came when my wife answered the phone one day when I was doing phone interviews collecting comments from musicians about Roy Orbison, who had just died. Leslie later told me that she picked up the phone and a British voice said, “Is Michael Goldberg there?” She said, “Can I tell him whose calling?” The man said, “George Harrison.” I’d interviewed a lot of musicians by then, but former Beatle George Harrison. Wow! I felt like I had felt when seeing the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show when I was kid.

Seattle Star: What’s in your future, after promoting this book?

Michael Goldberg: I’m working on another book currently. I can’t say anything about it at the moment, but I’m really excited about it. It’s a music book.